Preview of Featured Article:

"Political Islam and the Endurance of American Empire"

by Abdullah Al-Arian

Last year, Lebanon held its first parliamentary election in nearly a decade. Following years of political gridlock that featured the collapse of multiple cabinets, saw the country without a president for over two years, and included the momentary resignation of its prime minister as he was being held captive on foreign soil, in May 2018 Lebanese citizens were finally able to return to the polls. A year earlier, Lebanon’s political factions had agreed on a new electoral law, one that was set to introduce some elements of proportional representation to the country’s winner-takes-all system. Most of the discussions around the intricacies of the new law focused primarily on the possibility that it could empower new actors and break the traditional elite’s stranglehold on the political system.

But buried deep in the electoral law was a curious provision. In the section governing election financing guidelines, one article stipulated that every candidate for parliament was required to finance their campaign using an account in a Lebanese bank and submit that account for public audit—a standard requirement for most electoral systems. Further down in this section, the law stated that where “‘for reasons beyond their control,’ a candidate or list cannot open or use a bank account, funds for that election campaign must be deposited ‘in a public fund established by the Ministry of Finance, which shall replace the bank account in all aspects.’”

This addendum was included to allow a prominent actor on the Lebanese political scene, Hizballah, to participate in the upcoming elections. Not only was Hizballah expected to contest the parliamentary elections, its bloc was projected to (and eventually did) make significant gains in the new parliament. But without writing in a loophole to the electoral law that essentially created special dummy accounts within the Lebanese Central Bank, Hizballah-affiliated candidates would not have met a basic eligibility requirement to run for parliament.

Although the law never explicitly stated this, the reason this provision was included was in an attempt to observe international banking regulations that prohibit local banks in Lebanon from granting accounts to members of a movement deemed by the United States to be a “terrorist organization.” The United States first designated Hizballah as a terrorist organization in 1995. But it was only after the attacks of September 11, 2001 that the Department of Treasury instituted a series of regulations intended to combat global terrorist financing. These included carefully monitoring local and international financial transactions, freezing assets, issuing sanctions against specially designated terrorists, and enforcing penalties against international financial institutions found to have enabled any transactions involving a designated organization or individual. To do so effectively, the U.S. government had to enlist the cooperation of various international institutions, such as the United Nations, and the governments of nearly every country in the world, even though the UN does not officially recognize terrorist designations, and most countries have not designated Hizballah as a terrorist group (some European and GCC states did so in 2013).

"Political Islam and the Endurance of American Empire"

by Abdullah Al-Arian

Last year, Lebanon held its first parliamentary election in nearly a decade. Following years of political gridlock that featured the collapse of multiple cabinets, saw the country without a president for over two years, and included the momentary resignation of its prime minister as he was being held captive on foreign soil, in May 2018 Lebanese citizens were finally able to return to the polls. A year earlier, Lebanon’s political factions had agreed on a new electoral law, one that was set to introduce some elements of proportional representation to the country’s winner-takes-all system. Most of the discussions around the intricacies of the new law focused primarily on the possibility that it could empower new actors and break the traditional elite’s stranglehold on the political system.

But buried deep in the electoral law was a curious provision. In the section governing election financing guidelines, one article stipulated that every candidate for parliament was required to finance their campaign using an account in a Lebanese bank and submit that account for public audit—a standard requirement for most electoral systems. Further down in this section, the law stated that where “‘for reasons beyond their control,’ a candidate or list cannot open or use a bank account, funds for that election campaign must be deposited ‘in a public fund established by the Ministry of Finance, which shall replace the bank account in all aspects.’”

This addendum was included to allow a prominent actor on the Lebanese political scene, Hizballah, to participate in the upcoming elections. Not only was Hizballah expected to contest the parliamentary elections, its bloc was projected to (and eventually did) make significant gains in the new parliament. But without writing in a loophole to the electoral law that essentially created special dummy accounts within the Lebanese Central Bank, Hizballah-affiliated candidates would not have met a basic eligibility requirement to run for parliament.

Although the law never explicitly stated this, the reason this provision was included was in an attempt to observe international banking regulations that prohibit local banks in Lebanon from granting accounts to members of a movement deemed by the United States to be a “terrorist organization.” The United States first designated Hizballah as a terrorist organization in 1995. But it was only after the attacks of September 11, 2001 that the Department of Treasury instituted a series of regulations intended to combat global terrorist financing. These included carefully monitoring local and international financial transactions, freezing assets, issuing sanctions against specially designated terrorists, and enforcing penalties against international financial institutions found to have enabled any transactions involving a designated organization or individual. To do so effectively, the U.S. government had to enlist the cooperation of various international institutions, such as the United Nations, and the governments of nearly every country in the world, even though the UN does not officially recognize terrorist designations, and most countries have not designated Hizballah as a terrorist group (some European and GCC states did so in 2013).

Table of Contents

F E A T U R E D A R T I C L E

Political Islam and the Endurance of American Empire | 7

Abdullah Al-Arian

A R T I C L E S

Racial Capitalism and the Campaign Against “Islamo-Gauchisme” in France | 12

Muriam Haleh Davis

The Absence of Coptic Christians on the Rabaa Square | 16

Mina Ibrahim

How the Saudi Regime Silences Those Who Discuss the Khashoggi Affair Online | 20

Marc Owen Jones

UNRWA and Palestinian Refugees Under Attack: When Politics Trump Law and History | 22

Francesca Albanese

Ali ‘Abd al-Raziq: A Profile | 25

Andrew McDonald

Iraqi IDP Returns to Former ISIS-Held Areas: Findings from a Longitudinal Study on Durable Solutions | 28

Rochelle Davis, Grace Benton, Dana al Dairani, and Michaela Gallien

S P E C I A L F E A T U R E : S U M M E R O F C O U P S

Introduction | 32

Jadaliyya Editors

The Invisible Line: Soldiers and Civilians in the Middle East | 34

Drew Holland Kinney

Regime-Security Urbanism: Cairo 2050 & Beyond in al-Sisi’s Cairo | 38

Robert Flahive

Academics for Peace Continue Standing Trials: An Interview with Murat Birdal | 41

Anya Briy

NEWTON Bouquet, “Summer of Coups” | 46

NEWTON Editors

Summer of Coups Series: From the Jadaliyya Archives | 48

Jadaliyya Editors

P E D A G O G Y

Roundtable: The Future of Political Islam in the Middle East and North Africa under the Changing Regional Order | b

Francesco Cavatorta, Courtney Freer, M. Tahir Kilavuz, Peter Mandaville, Samer Shehata, and Stacey Philbrick Yadav

Decolonizing Middle East Men and Masculinities Scholarship: An Axiomatic Approach | 62

Frances S. Hasso

Essential Readings: Authoritarianism | 67

Steven Heydemann

Essential Readings: Said’s Orientalism, Its Interlocutors, and Its Influence | 70

Anthony Alessandrini

A R A B I C

القبيسيات في السياق المجتمعي السوري - الجزء الثاني

Sawsan Zakzak سوسن زكزك

81

تأملات في الغياب: الأرشيف الفلسطيني من حركة التحرر إلى دولة أوسلو - الجزء الثاني

Hana Sleiman هنا سليمان

86

موت مجرم آخر: عن بوش الأب

Sinan Antoon سنان انطون

97

R E V I E W S

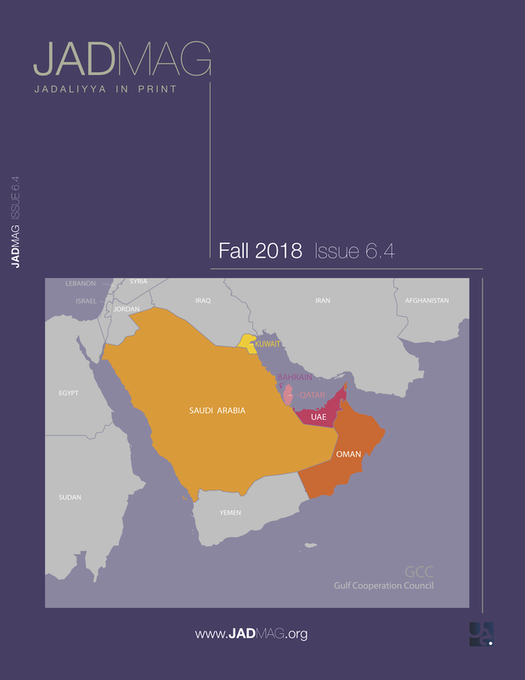

Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (New Texts Out Now) | 98

Adam Hanieh

“How I Met My Great-Grandfather: Archives and the Writing of History” (New Texts Out Now) | 101

Sherene Seikaly

The Proper Order of Things: Language, Power, and Law in Ottoman Administrative Discourses (New Texts Out Now) | 102

Heather Ferguson

“Labor-Time: Ecological Bodies And Agricultural Labor in 19th-and Early 20th-Century Egypt” (New Texts Out Now) | 106

Jennifer L. Derr

I N T E R V I E W S

Israel, Human Rights Watch, and the Nation State Law: A Conversation Between Bassam Haddad and Omar Shakir, Israel-Palestine HRW Director | 110

Bassam Haddad

F R O M T H E A R C H I V E S

Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis | 116

Mouin Rabbani

A B O U T T H E A U T H O R S | 126

M O R E F R O M T A D W E E N | 130

F E A T U R E D A R T I C L E

Political Islam and the Endurance of American Empire | 7

Abdullah Al-Arian

A R T I C L E S

Racial Capitalism and the Campaign Against “Islamo-Gauchisme” in France | 12

Muriam Haleh Davis

The Absence of Coptic Christians on the Rabaa Square | 16

Mina Ibrahim

How the Saudi Regime Silences Those Who Discuss the Khashoggi Affair Online | 20

Marc Owen Jones

UNRWA and Palestinian Refugees Under Attack: When Politics Trump Law and History | 22

Francesca Albanese

Ali ‘Abd al-Raziq: A Profile | 25

Andrew McDonald

Iraqi IDP Returns to Former ISIS-Held Areas: Findings from a Longitudinal Study on Durable Solutions | 28

Rochelle Davis, Grace Benton, Dana al Dairani, and Michaela Gallien

S P E C I A L F E A T U R E : S U M M E R O F C O U P S

Introduction | 32

Jadaliyya Editors

The Invisible Line: Soldiers and Civilians in the Middle East | 34

Drew Holland Kinney

Regime-Security Urbanism: Cairo 2050 & Beyond in al-Sisi’s Cairo | 38

Robert Flahive

Academics for Peace Continue Standing Trials: An Interview with Murat Birdal | 41

Anya Briy

NEWTON Bouquet, “Summer of Coups” | 46

NEWTON Editors

Summer of Coups Series: From the Jadaliyya Archives | 48

Jadaliyya Editors

P E D A G O G Y

Roundtable: The Future of Political Islam in the Middle East and North Africa under the Changing Regional Order | b

Francesco Cavatorta, Courtney Freer, M. Tahir Kilavuz, Peter Mandaville, Samer Shehata, and Stacey Philbrick Yadav

Decolonizing Middle East Men and Masculinities Scholarship: An Axiomatic Approach | 62

Frances S. Hasso

Essential Readings: Authoritarianism | 67

Steven Heydemann

Essential Readings: Said’s Orientalism, Its Interlocutors, and Its Influence | 70

Anthony Alessandrini

A R A B I C

القبيسيات في السياق المجتمعي السوري - الجزء الثاني

Sawsan Zakzak سوسن زكزك

81

تأملات في الغياب: الأرشيف الفلسطيني من حركة التحرر إلى دولة أوسلو - الجزء الثاني

Hana Sleiman هنا سليمان

86

موت مجرم آخر: عن بوش الأب

Sinan Antoon سنان انطون

97

R E V I E W S

Money, Markets, and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (New Texts Out Now) | 98

Adam Hanieh

“How I Met My Great-Grandfather: Archives and the Writing of History” (New Texts Out Now) | 101

Sherene Seikaly

The Proper Order of Things: Language, Power, and Law in Ottoman Administrative Discourses (New Texts Out Now) | 102

Heather Ferguson

“Labor-Time: Ecological Bodies And Agricultural Labor in 19th-and Early 20th-Century Egypt” (New Texts Out Now) | 106

Jennifer L. Derr

I N T E R V I E W S

Israel, Human Rights Watch, and the Nation State Law: A Conversation Between Bassam Haddad and Omar Shakir, Israel-Palestine HRW Director | 110

Bassam Haddad

F R O M T H E A R C H I V E S

Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis | 116

Mouin Rabbani

A B O U T T H E A U T H O R S | 126

M O R E F R O M T A D W E E N | 130